CRITICS

By Juanjo Izaguirre,

Buenos Aires, Autumn 2017.

Just as the New York exhibition celebrates its 100th anniversary, in which Marcel Duchamp exhibited his famous work ‘Fuente’ and which changed the meaning of the visual arts forever, the Uruguayan artist Anna Rank not only restores the plastic value of the line and the human figure, but also defies its limits and, at the same time, keeps alive the legacy of Joaquin Torres Garcia and his ‘Escuela del Sur’.

In the work of Anna Rank there are permanent presences. Geographies and concepts with proper names, or proper names that are themselves or become concepts and geographies. Geometry, deconstruction, Dominican Republic, the School of the South, New York, bidimension, Puerto Rico, tridimension, Paris, relief, emptiness, Montevideo, the rational and the game, Buenos Aires, Joaquin Torres Garcia and Jacques Derrida. All of this is communicated through a line and always with a human figure as a landscape and a permanent presence.

“It’s true that my parents studied at the Taller Torres-Garcia. They were both artists. My mother was a painter and my father a set designer. I had the opportunity, as a child, to be surrounded by the fantasy of theatre and painting. I therefore got to know the School of the South from within.”

And so the journey of their artwork began by means of a daring line, one that questions the limits of logical anatomy and technical support, and which makes us lose ourselves and find ourselves in natural and surprising places.

“At the beginning I did not want to be an artist like my parents, of course. I painted hidden constructions, mainly using triangles and curves as a rebellion against the vertical and horizontal lines taught by the Taller Torres-Garcia.”

Today, however, geometric structure is discernible and perceived in the construction of Anna Rank’s images, like a subconscious presence, which sustains the sensuality and the ease of her lines and strokes. And there is a reason why.

“Geometry is the scaffolding that builds the work. It can either be seen or not. It can be found just as much in a geometric painting as in a figurative one. It is what structures the work and what sustains it.”

But it is not only the arithmetic conception of geometry that sustains the work of Anna Rank.

“The Humanism of Torres-Garcia, expressed through Constructive Universalism, taught me to work the geometric-organic composition; and the Post-Humanism, with its idea of Deconstruction, helped me visualise the human figure composed of various images which shaped my anthropomorphic signs.”

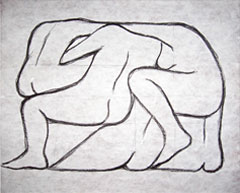

Anna Rank’s exhibition, “Human Symbols” at the Cultural Space of OEI, is composed of four series, which could well be considered to be four plastic challenges which simultaneously raise the aesthetic concept of ‘unity’ in the aesthetic development of their searches and their intention to push the limits of the value of ‘the line’, and of the human figure, as a theme.

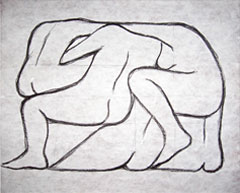

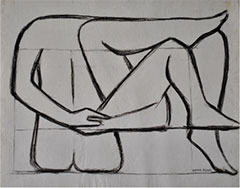

On the one hand, there are her drawings and paintings. Firstly, from the bidimensional where Anna Rank demonstrated the maturity of her trade, there is the security and sensuality of the stroke and the security that gives Anna her geometric ‘expertise’. On the other hand, there are her ‘reliefs’, which show her challenge of taking her knowledge of the picture plane above and beyond, and her intention to involve herself in the game of overcoming formal limits posed to her by the development of her images.

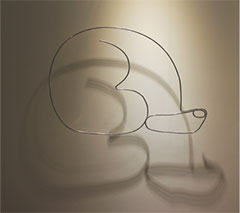

In the series of ‘the wires’, she takes the possibilities of the line to the extreme, as an instrument and as a plastic value, maximising its reach, playing with the light, the shadow, the background, and the point of view of the spectators, making them essential factors of the work.

Lastly are ‘the stamps’, which breaks all exhibition patterns, entering and incorporating the space and crossing the path of each spectator. How would you describe the evolution of your images and your work from the era of the School of the South to your work today?

“I really think that for a strange reason the two are coming closer together as time goes on. The curve of the wire bodies are references to the curves of my first paintings and the stamp series ‘Human Symbols’ are references to the anthropomorphic geometry that has always fascinated me in the pictograms of the pre-Columbian culture, and that Torres Garcia urged us to investigate in his teachings.”

Technique-image or image-technique? Which leads to which? The hand to the mind or the mind to the hand? In your case, which is stronger?

“I think that in my work, technique and image give back to each other. In the case of a relief, I can discover an image because of the technique. And when drawing and working with wire sculptures, I have an image and the technique synthesises it and multiplies it in a counterpoint between form and emptiness.”

In the series ‘Human Signs’, using the wire, you take a step further by playing with the line, the light, the shadow and the position of the spectator. How did the process of discovery and experimentation of the resources finally make you take the decisions that led to the realisation of the series?

“In the installation ‘Spectrum’ I had already played with the projected shadows of branches, and it was an incredible experience to see the spectator inside of the branches. Trapped again in the bidimensional of drawing, I needed to escape the plane, and the idea of wires and emptiness and multiple lines appeared; it was a new world for me, and a world that I continue to explore.”

Tell us about the stamps.

“Torres Garcia, from Uruguay, urged his students to investigate archaic cultures, especially the Pre-columbian; not to copy them, rather to work our own images in their mediums.

I worked with collectors of Pre-colombian art in New York and in the Caribbean. I mainly studied the Tainos and their wonderful petroglyphs, which I incorporated into clothing projects. Years later, during my scholarship in Paris, the anthropomorphic images began to appear in museum collections again, as much in the archaic Pre-colombian culture as in the Mesapotamian, through stamps that fascinated me for their artistic and communicative versatility and which inspired me to start the project ‘Human Symbols’. In this series, I return to clay, working in stamps. They are extremely synthetic reliefs. I print their images like the Pre-colombians did, onto leather, onto fabrics, not only creating a print but also an embossing, multiplying the image.

You work very closely with Nadia Paz, your curator. How did that link work? Do you think the role of the curator together with the plastic artist is important, as in the case of the producer with the musician, or the editor with the writer?

‘Nadia Paz, for years, has assisted me enriching my didactic and theoretical projects. She is an artist and was a student of mine. Therefore, she knows the School of the South from the inside. That is what enables her to understand all of my comings and goings between Construction and Deconstruction, through reason or by instinct. Nadia understands my work from her constructive experience, and she has the magic to visualise it and communicate it.’

Emptiness and presences, limits and challenges, structures and games, sensuality and geometry, yesterday and today, opposites which complement each other and similarities that provoke each other. All that is in Anna Rank’s ‘Human Symbols’. Like in an amusement park, in between joy and reflection.

By Nadia Paz,

April 2017

To construct or deconstruct, that is the question. The work of Anna Rank, with its synthetic and geometric lines, includes the empty space as part of creation and gives it a new entity. It freezes centuries of culture in a single line and renews the Latin American spirit born from the origins of the pueblos. The symbology recovered transforms and reflourishes in the form of our own bodies, producing an encounter mirrored in our roots. It reminds us of what we were, what we are and presents us with an apparent vacuum that questions the near future, in which we should choose what we will be.

It reminds us that we are free, that we are permanently in motion and the transformation should, deep down, contain a preterit drop of what our previous generations have done for us. The human symbols are visual representations of those signs that our own construction constantly leaves behind.

By Nelly Perazzo,

September 2016

Anna Rank’s work always has a point of reference: the human figure.

Her command of the line, when it is separated from the support and seems to float in space, allows her to objectify a very particular energy.

These bodies, limited by their graceful outlines, to not answer to anatomical logic. Rather, they raise questions.

The use of light doubles their limits and the displacement of the spectator means they enter a dynamic, multiplying game.

ANNA RANK, ONEIRIC READINGS

Alianza Francesa, Buenos Aires, 2015

(…)The purpose which guided him was not impossible, but it was supernatural. He wanted to dream a man, he wanted to dream him in minute entirety and impose him on reality. This magic project had exhausted the entire expanse of his soul; if someone had asked him about his name or some detail of his former life, he would not have been able to respond.(…)

Jorge Luis Borges

The Circular Ruins

The history of art shows us that since prehistory to the present day, the human figure has been evoked with a wonderful visual synthesis. Today’s artists, like our grand maestros, continue to be fascinated with this subject that broadly represents life. Its hieratic magic continues inspiring the creation and discovery of an infinity of lines, rhythms, spaces, planes, values and colors, all immersed in a deep vitality. A tremendous challenge that intrigues with its mysteries.

The work that I have developed in these recent years has always been seen as influenced by the both the natural and urban environment and has been expressed in different visual languages. The works presented here have been elaborated and matured from the point of drawing, sculpture and the image in movement. Inspired by our own natural state, they resemble beings lovingly interwoven in an atemporal environment, appearing and disappearing in a continual fluctuation of forms.

I draw on different techniques to be able to reconstruct the visual phenomenon and in this way be able to establish the opposing concepts of man-woman, light-shadow, abstraction-figuration. Departing from one we arrive at the other in a continual evolution of forms and spaces, generated thanks to the harmony of the human body.

As the maestro Joaquín Torres-García taught, seeking to arrive at a truly synthetic art, not just imitative, constructs an imagine rooted in the reality of its geometry.

ANNA RANK: THE OTHER SIDE OF THE LANDSCAPE

by Fernando Ureña Rib

Green, how I love you green

Federico García Lorca

In her eyes the world is a scene of greens that seek their way to the river. A route inverted towards the origin, towards wisdom, towards roots, towards the earthly essence that it forms with its biological data of woods or algae, of eternal substances that generate life.

There’s nothing strange about this. Anna Rank was trained as an artist beneath the shade of a powerful tree in the cracked landscape of the Western art of our times: Joaquín Torres García. For the maestro there were no mid points. The landscape was a continual succession of planes.

But Anna Rank opens questions. She leaves doubts. Her images seek to (and succeed in) unsettling us. What are we doing, you and me, today, with the landscape? What have others done? Until when? What superhuman force will impose their designs?

The force of this deep lament beats at the heart of the work of Anna Rank, for whom beneath the landscape beats, pulses and breathes the anguish of a cry for a renewed action that protects our essential environment, our scant possibilities of existence.

On the other side of the landscape of man. Man as a symbol of confrontation, as a symbol of struggle. Woman on the other side of man as a symbol of continuity and stability, as a pillar in the tradition of life, as a pillar of its conservation.

With Anna Rank nothing is casual or fortuitous. Moments happen until they reach the lofty peaks where reason, liberated from its tempestuous inquisitions, decides to rise up above itself, reach upwards, flying to utopian lands where hope is still possible.

ANNA RANK, PORTRAIT OF THE OMBU

by Cecilia Buzio de Torres

In October 1997 I visited Anna Rank at her studio in one of those corners outside of Montevideo that seem forgotten by time and untouched by the destructive action of "progress". After going through an old iron gate you enter a park where the view of the native ombu trees produces a surprising effect; we are accustomed to seeing imported fir trees from Sweden or eucalyptus trees from Australia in our gardens, not the native ombu trees. It was presumably Anna's reencounter with the ombu trees, after many years of studying and working abroad, that inspired her. They caught her attention when she returned; she didn't have to search for anything because what she was after were right in front of her in her own garden. Literally and metaphorically, the trees showed her the way to work and were a starting point for a theme that was, for her, authentically and faithfully represented by something that belongs to us. This work is similar to the landscape painting tradition of Figari, De Simone, Cuneo and Etchebarne Viart, all of whom painted ombu trees, but Anna gives the trees new life and turns them into something current. Symbolically, the ombu is an emblem of this region since it is often transformed into art. Anna has investigated records in both botanical studies and literature in order to rescue the ombu tree from the prejudices that we have often heard; for example, they don’t produce fruit, the wood is no good, it's a useless tree. For her, the ombu turns into a challenge, not only to find a way to paint it again, but also to reclaim it. Planting the easel in front of the ombu, according to Anna, isn’t a step back to the times of the impressionists’ "plein air", rather she works to establish live contact with the model, in order to later retire to the studio and rework what she did outside. "I rely on reality, that way I rescue the shapes and the values", Anna tells me when I notice that there is something of human bodies, members and shapes in this work, where the reference to the original is difficult to identify, even though the branches and leaves are real-size on the canvas. Why call these paintings portraits, and not landscapes, if they are of trees? The scale, which is faithful to reality, is an important element that characterises these works, as in the traditional landscape artist is rarely capable of painting the original size of things. In front of the tree, Anna must "find the painting", as the painters of the School of New York used to say, but unlike them, who "found" the canvas already painted, moving it around until they found the area that they liked the most, Anna finds the work within the live model, just like a portrait painter. Besides, her understanding in the powerful motif is so complete that for Anna each tree has an individual personality. The great size of the ombu painting is precisely a requiem for an elderly tree that dies slowly. When commenting that I was impressed by the tragic resemblance of the painting, Anna explained to me that one of the ombu trees that was already over 200 years old, lost a big branch; first it turned reddish, then whitish and in the end, the sap bled through the cracks of the bark. The palette in these paintings, in spite of how light and clear it is in appearance, is the product of many colours. Anna counts on the transparency of the white canvas, and unlike the old masters, she keeps the palette light and bright because she starts by establishing the darker shades first, using little black in her works. She achieves the dark parts with dark brown or sometimes deep reds and the opposition of warm and cold colours she achieves through painting the effects of light and shadow. Each colour has an essential quality, she explains, lemon yellow is colder than chrome yellow, and knowing the scale and the values of the colours, she can apply them without mixing. In fact, she superimposes them so that she creates a sound, clear and vibrant surface. It’s surprising the colours she dares to incorporate in the most unexpected places, when you come closer to the canvas and you encounter a venetian red in the trunk, for example, or soft touches of alizarin, rose madder, cerulean green and ultramarine blue. The brush-strokes are wide, energetic, and almost surprising because of their vigour; they are not exactly "feminine" in the conventional sense. Anna confesses she spends a lot of money on paint brushes, and that she needs a lot of physical space to paint because she has to constantly go backwards to see with a certain distance the way the colours and the brush-strokes compose shapes. This is not the art of a miniaturist; it's an affirmative and active painting. In the charcoals you have big black strokes that are firm, direct and reviewed over and over again; the positive and negative shapes of the trunks and the absence of colour reveal the drama contained in the canvas. When observing the charcoals carefully you can see a framework of slightly visible octagonal lines that go through the canvas in horizontal and vertical directions, which demonstrates how her work is supported by a rigorous structuring and that such temperamental and expressive strokes are controlled by a will of imposing equilibrium between reality and abstraction, emotion and reason. Besides, Anna likes to intrigue us with combinations and tricks for the eyes hidden in her works. For example, in the triptych each 1x1 metre unit is an independent drawing, but when you hang them together in any combination, the lines of the branches relate to each other perfectly, and the total work shows us the deep intelligence of its conception.

THE OMBU

"An existential testimony"

by Guillermo Roux

The theme of Anna Rank’s paintings is the tree, more precisely the ombu tree; that strange and ambiguous plant, halfway between a tree and a bush that grows in our lands. With its foliage and roots, it provides necessary shelter in the infinite flatland as well as a reference point in the loneliness of the green pampas.

If the represented images are a projection of the internal images of the artist, I don’t doubt that for Anna Rank, the ombu trees symbolize the affirmation of their belonging. A belonging to the Rio de la Plata, conflictive like ours, that sings and cries in her paintings. The ombu is a sign that indicates her angst for the uncertain destiny of man and, by her own transition, as a woman and as an artist in this moment in time.

Anna Rank chose the ombu trees to show us her own soul, and this demonstration is so poignant that she adjusted her visual language to what each part of this existential itinerary had to say.

This determination as a painter and attempt to ignore prejudice, which has been imposed on her every second of her life, is precisely how important and personal an artist Anna Rank is. She paints paintings that are at times conventional, at others are luminous and sensual like a summer afternoon and yet others that are dramatic and solemn like the echo of a Bach requiem. This set of works does not lose unity nor does it contradict itself. Anna Rank can express all these feelings because she has a solid purpose. We know that her master was the great painter Julio Alpuy and that he taught her the legacy of Torres Garcia's studio. In my opinion she couldn't have had a better artistic education, that's why her work, as I previously mentioned, has an extensive range of possibilities. She can paint pure shapes, almost abstract, as well as the light, without losing the healthiest principles of visual construction.

Fundamentally, we are talking about the tree. Anna Rank is a new and vigorous sprout of a trunk that has given life to such extraordinary Uruguayan and universal painters.

In these times of confusion and rush, of false values and frivolousness, we must thank and take care of this painting, which is full of existential pathos, in order to prevent a bad weed choking it.

SPECTRUMS OF THE TREE

by Raúl Santana

The drawings and the installation that Anna Rank presents today, in addition to being an adjusted visual chant, are constellations that acquire the dimension of the symbolic, through which an artist puts us in front of nature.

Her fragmentary representation of trees, her sculptural formal inventions revaluated in vinyl, are a part of the same project; in front of the devastation that the modern world is causing to the environment, she points almost obsessively to endangered species and immobile inhabitants of the Rio de la Plata that sometimes, in their artists’ interpretations, could be confused with true anthropomorphisms, which watch over the landscape with the magnificence of their existence.

"Spectrums of the Tree" is the name Anna Rank chose for this poetic and sensitive homage in which reality and imagination unite to illuminate with splendid formal wealth this alarming aspect that constitutes one of the great pending issues of life nowadays.

THE COMBINATION OF COUPLES

by Julio Alpuy

It is with great satisfaction that I talk about Anna Rank. It reminds me, with much affection, of the time she was living in New York and of the work that we did together, an experience that was as useful for her as it was interesting for me.

Anna is a natural artist. From the very beginning her talents were clearly demonstrated and her intelligence was evident. I was both excited and pleased to take her on as a student. It was a pleasure working with her, as she absorbed knowledge with great speed and understanding. Very few of the many students I have had were able to easily grasp the principles of art. It is true that this is not easy, given that it is not only a question of understanding these principles but also understanding their importance nowadays, as the tradition has been forgotten, its concepts have been distorted and young artists don’t grasp its importance. Anna understood all of this with astounding ease and we were able to develop her work on a different level, different in this case meaning that from the very start she was working on notable pieces. We worked very successfully together for eight years, reaching very early on a level of progress that pleased me greatly. And it is for this reason, as well as our friendship, which is so close that I consider her family, that it is a pleasure to see Anna in New York year after year.

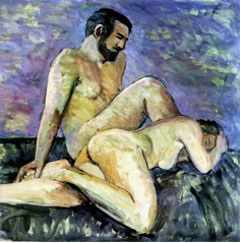

Apart from this, I want to say something about her work. From the start, Anna demonstrated quality in her work. I can’t forget her first nudes, the interpretation of tone, the composition and the character of her paintings. Tone is priority in painting (to say “tone” is to say “painting”). They are one and the same. Anna not only understood this quickly, but I discovered that it was innate within her. What was really innate within her was the quality of painting. Anna is a painter, was born a painter. My aim has been that which every teacher should have: to guide her along the correct path. From the start I have seen her evolution. With great interest I have followed her and I have always found not only success but continual exceedance. I can vividly remember a series of paintings inspired by an ombu tree that she had in front of her window, when the winter prevented her from going out. Her incredible richness of imagination drew so many possibilities and so many varied forms, unimaginable tones in each of the paintings, which means that the same tonalities of the ombu tree were seen in a different way in each piece, yet always remained authentic.

Anna’s passion for painting nudes led her to combine the paintings of the ombu tree with the human body and she achieved some excellent paintings. In the current paintings, her evolution has led her to work almost exclusively with the nude figure and this combination of couples is wonderful. The composition of these paintings is very exact, carried out with grace. And if we talk about tone and the variation of the palette, we can see that she has a great deal of creativity.

I was extremely impressed when I saw her latest work. Well done Anna! This will go from strength to strength, I am sure. New York, March 2006.

ANNA RANK, SKETCHES AND PAINTINGS

Sarah Guerra, Curator (AACA-AICA)

Who has said that drawing is the writing of the shape? – said Manet – The truth is that art must be the writing of life. This suggests that drawing is not only the precision of the shape, but the deep expression of being. It is no less true that without a comprehensive dominion of shape the expression will not be convincing.

Anna Rank, draughtswoman and painter, reunites the conditions to reveal life at its peak in her work. The nudes and the ombu trees find themselves structured with adjusted rigor and, at the same time, propose a game of shapes and sensitive spaces. The nude is the ideal state, whereas clothes reflect beauty and truth and it is said that truth should be without veil.

In these works, as much as in the emblematic ombu trees, Rank transcends the natural exterior because she searches for an order to accomplish the living structure. Drawing means the search of the expressive shape, with colour finding the tone that constructs harmony between shape and space. Anna is faithful to nature, both in landscape and human figures, not copying, only recalling in her artistic understanding. She does it from the unity of her being, which is the evidence of genuine creation.

ANNA RANK

The solution to the mystery is always inferior to the mystery itself

Jorge Luis Borges, El Aleph

by Cristina Dompe - March 2012

Anna Rank’s artistic world, which has taken many different routes, unveils to us the steps of her rich visual trajectory; from Buenos Aires to the Torres Garcia School in Uruguay to the Parsons School in New York to the intensity of Caribbean, but what remains fundamental to her work is her artistic outlook on man and his world.

There is also the ductility of the technical resources with which she expresses her thought. The reflexive oil she uses in her paintings, the fast and light charcoal for her drawings, the re-naturalization of the materials for her reliefs, and the whole wide spectrum of color that she covers, from the saturated tropic to the black and white drama or the absolute black or white, that equalizes the differences and increases the mysteries.

Her work "Fragments of Being" forms a suggestive enigma with neither time nor order permanent in the unit, in which every segment is connected with each other and in which every itinerary is free and possible. In the tribute to the Ombu, where the bark turns into skin; in the disturbing Ciguapas, with little tree inhabitants, mythical human chasers that never come back; the Couples with their countless courtships and finally the organic assembly and the continuation of legs and arms barely recognizable in the artist’s last reliefs, are complementary metaphors of enormous aesthetic value.

Cecilia de Torres

December 1995

Contemplating an old ombu in the garden of her house, I understood what had motivated Anna Rank to paint and draw sections of those thick branches, reminiscent of the limbs of a human body.

The ombu tree has a form that those born in these South American planes immediately recognize and that identifies us. Anna’s great originality, using these trunks as a model, is that as well as yielding them great visual possibilities, they are also a symbol. Of return and belonging.

Her rigorous training, first with Julio Alpuy and then at the Parsons Institute, taught her to not be carried away by the sensualism of naturalist imitation, and for this reason both the ombus and the nudes that Anna paints are carried out with great economy of pictorial medium to give expressive capacity with the greatest synthesis. Nevertheless, observing these canvases up close you discover a palette rich in combinations of unusual, perfectly toned colors used with daring. Unlike severe charcoals, they are executed with an almost expressionist technique, indicated by the accent of the clean line and the energetic gesture.

This work marks a new chapter in the tradition of our painting, as we discover the endless possibilities of a medium that announces itself periodically, and to which artists like Anna Rank give new life.

Julio Alpuy

New York, July 11th 1994

Objectivity in painting, like in any circumstances in life, is a fundamental coincidence, a quality that is rarely found nowadays and that is a principal base of any work of art. This quality is very evident in Anna Rank’s work.

There is always a truth in her painting that fortunately removes her from all fantasy. There is never anything false in her work, and for this reason she creates affirmative, concrete paintings.

Her vision combined: large plains, large lines that construct the scene, always seeking synthesis, which is abstraction and unity.

All these are qualities of good painting, and Anna brings them together to create strong and original painting.

I have worked with her for many years and I confess that from the start I was impressed by her willingness to learn, her clear inventiveness and her creativity. Her painting has, without doubt, a great future ahead.

Marcela Berthe

Búsqueda, December 1994

“Majestic Ombus… Captivated by this giant plant with the complexity of a tree, the painter Anna Rank draws her gaze to the branches and her paintbrush recreates them naked, static, and majestic. Rank explores spectrums of vigorous greens in oil paints, explores their brightness and their depth to bring to the canvas a quality that is half abstract and half magical, which extracts the essence of the nobleness of the ombu”

Alvaro Martínez DoMonte

Ultimas Noticias, December 1994

“Anna Rank… Her pieces reach the spectator firstly and undoubtedly through the previously mentioned topic; but they seduce and entrap with the expressive force that the artist manages to give in each piece. The painter plots, performs, does and undoes natural elements and her own feelings on the surface of each canvas, but without falling into fantasy, and always with an experienced visual grammar and great control of drawing and color…”

Elisa Roubaud

El País, December 1994

“The ombu tree is the theme of this series; nevertheless the nude, the fundamental concern in previous works, is not absent; on the contrary, organic forms, whether human or plant, find in these compositions an interesting type of relationship that intimately integrates them… Anna Rank has a wide range of colors that go from blazing to a fresh glow, uncontaminated by any suspension in the atmosphere, a pure rhythm, ideal, even the glazing that compounds layers, that gives the painting another age, another depth…”

Mayling Carro Amorín

La Mañana, January 1995

“Anna Rank’s excellent painting… Ombu and human being for her are mixed up in this skin that she has executed with skill. Subtle skin, transparent, it is elevated in positive synthesis. … she has proclaimed in these “sectors” the maximum proximity of the reason of existence in tight embraces that belong to us in the country’s identity. Anna Rank could have established a sophisticated painting but she has rejected this tempting possibility…

Julio C. Carbajal

La Juventud, January 1995

“Anna Rank: Painting Constructing… Our traditional ombu, with an original treatment in which the artist fragments the object and reconstructs it in structures with great rhythmic value…”